Monday, September 21, 2020 from 6:00PM

Watch a recording

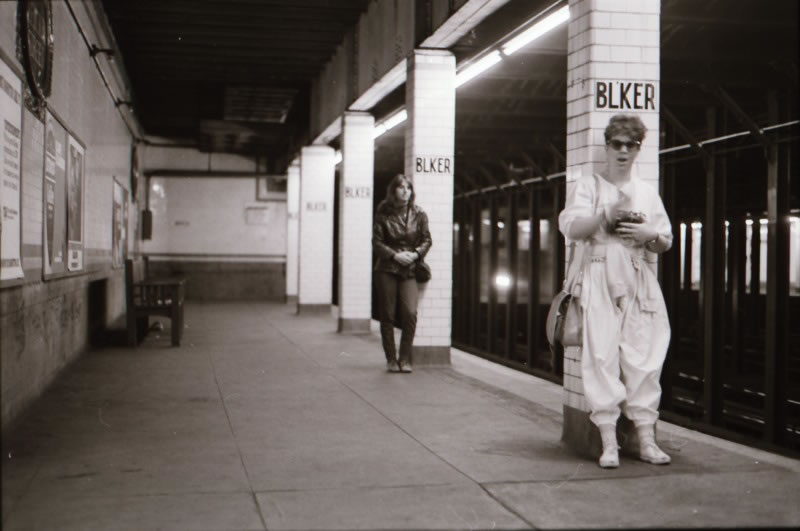

In the world photographer Meredith Marciano captured on film, the Twin Towers juxtapose with a graffitied Washington Square Park Arch; vintage signs in the East Village, ghost lettering in SoHo, and forgotten Mom & Pop stores across the city abound. Join us for this special presentation and talk with Meredith, where she’ll discuss her art-making process and 30+ years roaming the streets of downtown and New York to find the perfect shot.

Meredith Marciano has had a casting company in NYC since 1986 and is also an avid photographer. Trained in film at USC, she worked as an industry location scout in her native Boston, before settling in the East Village in 1984, where she has resided since. With a strong eye for pop culture, ephemera, and architecture, Marciano has created indelible images of the five boroughs and beyond. A collection of Marciano’s photographs, many of which capture sites and storefronts since sold, altered, or razed, can be found in our Historic Image Archive. Further historic photos from Boston and Los Angeles are available on Flickr, and more recent analog work can be found on Lomography.

Presented in partnership with Village Preservation

Interview with Meredith Marciano

There’s something about film… a warmth and a depth. It’s about the grain: it’s more tactile.

Meredith Marciano talks to Liz Thomson about her love affair with urban photography and old tech

“The only beauty’s ugly, man”, wrote Bob Dylan, back in the early 1960s, when he was still scuffling for dimes on the streets of Greenwich Village. The quote sums up much of Meredith Marciano’s work as a photographer – she finds beauty in urban decay, “the deserted, abandoned, falling-apart” buildings, the “ghost signs” which, like urban gravestones, mark the spot where citizens once bought their bread or dropped their laundry; the abandoned factories; the shuttered clubs and theaters; the rusting roller coasters and abandoned carousels.

“After they’re renovated, I’m not interested,” says Marciano, chatting via Zoom from the home near Springfield, Massachusetts, where she and her family have been living during the Covid crisis. “I’m sick of the woods as my photo backdrop!” she volunteers, having for a while enjoyed the novelty of dressing up friends in vintage clothes and photographing them – in colour, unusually for her – in more arcadian settings, all socially distanced. Hopefully, she will soon be back in the East Village, where she and her husband still keep the small apartment they lived in before the kids arrived and from where Marciano wandered the city, taking many of the photographs that form the basis for Capturing Downtown and Beyond: the Photography of Meredith Marciano, an online event with Village Preservation, to whose Historic Image Archive she has donated many photos, and The Village Trip. “I knew the organization, saw a link to their photographers and sent an email on spec, saying I had all these pictures of New York in the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties and were they interested.” They were, and she was happy to donate them, their interest “flattery enough. And it would be nice if they could profit from a photo sale.”

“After they’re renovated, I’m not interested,” says Marciano, chatting via Zoom from the home near Springfield, Massachusetts, where she and her family have been living during the Covid crisis. “I’m sick of the woods as my photo backdrop!” she volunteers, having for a while enjoyed the novelty of dressing up friends in vintage clothes and photographing them – in colour, unusually for her – in more arcadian settings, all socially distanced. Hopefully, she will soon be back in the East Village, where she and her husband still keep the small apartment they lived in before the kids arrived and from where Marciano wandered the city, taking many of the photographs that form the basis for Capturing Downtown and Beyond: the Photography of Meredith Marciano, an online event with Village Preservation, to whose Historic Image Archive she has donated many photos, and The Village Trip. “I knew the organization, saw a link to their photographers and sent an email on spec, saying I had all these pictures of New York in the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties and were they interested.” They were, and she was happy to donate them, their interest “flattery enough. And it would be nice if they could profit from a photo sale.”

The freedom to photograph what and whom she pleases is essential for Marciano, who doesn’t care for the angst that comes with commissioned work, though she’s always pleased when someone wants to buy or license a photo – she was thrilled when the art department of If Beale Street Could Talk found one of her Seventies’ street scenes and asked if they might use it. “I was walking around Greenwich Village and came upon the set of Can’t Stop the Music starring the Village People and took a few photos from the side lines, then I walked around the corner and I liked the street – Grove Street, west of Bleecker – and I just shot one frame. There were only a couple of cars, so you could see the buildings, fewer trees and no people.”

Marciano grew up in Massachusetts in a family that had no particular interest in photography but “we always had cameras and we took a lot of pictures and slides. We did a trip to Europe in 1973 and I remember asking for a camera so I could take pictures, and they got me an Agfa 110mm – what we used to call a pocket camera. I really liked using it and experimenting with it, taking pictures at night.” Experimenting is something she still does, happily admitting to a lack of tech knowledge and a preference for old technology and cheap cameras, including the Diana-F (medium-format – a sort of poor man’s Hasselblad) and other analog devices beloved of Lomographers.

“In high school, in my senior year, I started studying black and white film and darkroom work. I learned filmmaking too – I had a Super-8 film class and a film history class.” Towards the end of 9th Grade, after a late night watching Carol Baker play Jean Harlow in a biopic, Marciano became “infatuated” with old movie stars and old movies, an obsession she would revel in alone until she convinced one friend to accompany her to the revival cinemas to see double-feature classics. That led to her wanting to be in the film business. “I wanted to be in Hollywood, that was my dream.” Majoring in art, art history, photography and filmmaking in her senior year, she then headed to USC where, in her junior year she finally got into film production, writing and directing Super-8 and 16mm shorts solo and as part of a small crew. She did well, but lacking “connections” and the wherewithal to survive the wait-lists for even the lowliest entry-level jobs, Marciano spent her last two years in Los Angeles working in the office of a record store chain, enjoying free concerts and bringing home lots of records. Many of her friends were starting out in the record business too, so it was a grand time overall being young and part of the post-punk paisley underground scene.

All the while, she’d been taking photos, taking advantage of the USC or friends’ darkrooms. “There was so much cool stuff in the Seventies – it was crumbling deco facades, cheap thrift stores packed to the brim with 1940s – ‘60s wardrobe, and an ever-rotating weird cast of characters.” She remembers particularly an old building on Sunset Strip: “It’s always being used in movies and it’s fabulous now but all the time I was there it was deserted, abandoned, falling apart… A lot of things have just gone, all the smaller art deco buildings on the side streets of Hollywood. Not everyone thought they were beautiful then.”

Marciano left LA in ’84 and spent a few months travelling in Europe with her camera. Then she headed back to Boston, working as a PA in a studio that made commercials. A job in location scouting fed into her passions – downtown Boston in the mid-Eighties was not yet gentrified. “It was dark and deserted at night and you’d come across some neat little old places. Like everywhere, it’s all spiffy now.” Finally, while working on an Aerosmith video she was offered the chance of a gig in New York City. “I called the producer from the video, who said I could reach out if I ever wanted to come to New York and work. She was producing a low-budget movie and I could be assistant coordinator… $250 a week, from six in the morning till seven or eight at night, and lots of free pretzels, the one product placement. My first feature, full-time work for a few months, I thought I was rich!

“As assistant production office coordinator I had many responsibilities in that SoHo loft office, really learning on the job. I was in charge of renting all the production cars and we couldn’t leave them out on the street at night. SoHo was very quiet and not as safe as now. Very dark. It wasn’t trendy yet.” The job led to other productions, including a couple in Atlantic City, where she snapped “some very cool shots” of the crumbling boardwalk with its abandoned jazz clubs and restaurants. In Philadelphia for Rocky V, she scoped out old movie theatres – “they’re all gone now. I put many of these photos on my Instagram or Flickr page.”

From her base in the Village, Marciano walked the streets of New York, for hours on end, out early to shoot in the empty streets. “Just walking around, trying to capture the buildings and the signs just to have a record. In the Eighties there were still things from the Thirties, Forties and Fifties and you didn’t think they were just going to disappear.” She also captured daily life: kids frolicking in fire hydrants; ads for Old Gold and Beech Nut Tobacco (“A great chew”); memorials to Joey Ramone, George Harrison, and 9/11.

Most of it is in evocative black and white, Marciano’s preferred medium, not least because she can print it herself but because it’s timeless, and timelessness is what she aims to achieve. The kit is never fancy, just set-the-light-meter-and-shoot. For a long time her most beloved camera was a Minolta SRT-201 (“it got to feeling heavy after a while and I can’t believe I schlepped it everywhere”) and now she has a Ricoh, plus a couple of cameras bought at flea markets – “film cameras from the Nineties”. Digital holds no appeal, and the only digital item she owns is her phone. “Digital is very sterile to me., and the photos can feel nostalgic or ageless. It’s the difference between an LP and a CD.” She also likes playing around with old film found in the back of her fridge, seeing what effects she can produce.

Much of what Marciano’s spent her life doing is street photography, but she doesn’t consider herself “a street photographer” and sees the term as a debased currency. “You see these guys who think it’s cool to stand far away from women and photograph them eating or smoking, or on their phone. They’re not interesting photos at all. That photographer just has a nice camera and a long lens. And then there are the photographers who post twenty shots of a bird’s beak – some people don’t know how to edit, and they sign them all, like they’re great art. This is what digital photography has brought us. You used to have to think before snapping the shutter. Film was expensive, you didn’t want to waste a frame, and as one of my friends and models said when we were out shooting in Brooklyn a few years ago, ‘this is work!’ And she said that before I even bought her into the Lower East Side darkroom, where she learned the real tedious work. I don’t want to take a photo of that guy’s gazillion tattoos who is Instagram-ready, but if I saw a guy who was doing something really interesting then I might ask if I could photograph him.” Nor does she take pictures of the homeless: “I don’t want to exploit people without their knowledge.”

“I look through my viewfinder and if I don’t like what I see I don’t take the picture.”